The Daves would like to welcome Brandon Engel to our website with his wonderful entry on George Romero!

In the periphery of mainstream filmmaking, George Romero has been churning out controversial movies for nearly 50 years, starting with his pioneering film, Night of the Living Dead, in 1968.

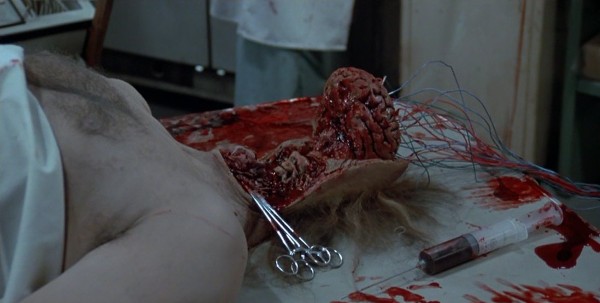

And even though it was shot in black and white and on a meager budget, Night knocked the socks off the viewing public. It received mixed reviews (with notable critics like Roger Ebert publicly expressing their distaste for the film, however effective it was) and it wound up essentially establishing the framework for the zombie film as we know it today. The film vividly depicted cannibalistic zombie feasts, and not only did Romero have the audacity to have his lead character played by a black actor (Duane Jones), but he also had the nerve to kill him off in the film’s screen. Not bad for a guy who launched his show-biz career on Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood.

So, was Romero’s foray into morbid storytelling a clever ploy to exploit a genre that hadn’t been tapped? Partially. He claims he belonged to a generation of people angry that the “peace and love” philosophy espoused by the era’s hippie generation wasn’t contagious enough to impact the rest of the American public. What better way to react to ongoing injustice than by turning loose a race of undead people skilled at not just scaring the pants off moviegoers but making important statements about society’s ill-placed priorities, too?

Fact is, political satire and social commentary in the late 1960s was beginning to impact media and Romero was delighted to channel his dissatisfaction into his films. His first movie, Night of the Living Dead, even had its own back story paralleling the film’s 1967 production: On the day Romero and crew arrived in New York to pitch the film to potential distributors, news broke that Martin Luther King had been assassinated.

Lots of movie makers jump from one genre to another, but George Romero understood his life’s work after “Night” opened to critical reviews in 1968. His characters populated all strata of society as he creatively articulated sociological ills via his creepy scenes. For example, “Night” included this powerful philosophy: if a world wants to survive zombies, people had better find ways to get along and abandon their self-interests.

A decade later, follow-up film Dawn of the Dead focused on the evils of conspicuous consumption and materialism, while his next production, Day of the Dead, sent a not-so-obscure message about the potential of a military-industrial complex becoming the driving force behind governance in a free society. Although it didn’t gain cult status as quickly as Night or Dawn, Day of the Dead was recently re-released on Blu-Ray, it’s also a highly popular streaming choice and as a DTV on-demand title (see their website), and the film will soon see its second remake, which should be going into production this year.

Given George Romero’s near-obsession with revealing the flaws in a country founded on free-market principles gone awry and consumerism driving society, it was no surprise to colleagues that he put race and ethnicity front and center when casting his films. By choosing an African-American actor over a Caucasian one, Romero could make equally strong statements about prejudice and discrimination.

Along the way, he mentored contemporary film greats like Danny Boyle (28 Days Later) and legitimized the idea of a race of peoples delighted to subsist entirely on human flesh while jerking along at a shamble. Romero’s zombies may have been incapable of forming coherent sentences, but a bullet to the head was all it took to stop them in their tracks.

No longer the lone voice on the zombie and horror film scene at the turn of the 21st century, George Romero expanded his already-prolific ideas about plots and scripts to include the controversial – like George W. Bush’s presidency (Land of the Dead produced in 2005) – using Dennis Hopper to tell a tale of jingoism and xenophobia. Taking a page from production crews experimenting with new techniques on projects like the Blair Witch Project and Cannibal Holocaust (2007), he wasn’t above borrowing and innovating his own versions of hand-held camera techniques and CGI effects.

Romero went on to direct another five films in the zombie canon, most recently 2009’s The Survival of the Dead. Romero tells his latest zombie tale which takes place in New York City in the form of a comic book. The Empire of the Dead, published by Marvel, is being published as a five-installment book.

In the “no regrets” department are Romero’s parodies Shaun of the Dead, 28 Weeks Later, Quarantine and subsequent remakes of benchmark films. Martin, Two Evil Eyes and Bruiser might not have topped lists of critics’ favorites, but they remain proud accomplishments. Oh, and of course he takes credit for being the force behind the modern zombie apocalypse craze that’s ushered in video games and hit TV shows like AMCs The Walking Dead. Romero told NPR reporters he believes videogames are responsible for cementing the place of the undead in pop culture, and so far, nobody’s disagreeing with his wisdom.

Have changing publication and broadcast formats and less-than-rave reviews dampened Romero’s spirit? Hardly. Romero knows that his place in the modern cinematic zombie movement is secure. He has no regrets about sympathizing with zombies who, courtesy of his insights, can be comical community members with specific roles to play and images to uphold. He has no intention of quitting the genre and isn’t hesitant to comment on the good, the bad and the ugly of current trends in horror filmmaking.

So, what’s up next for the filmmaker who still has goals to meet? Plenty. A continued battle to obtain financing for future films may be a factor in his ability to undertake more projects, but that doesn’t mean he’s given up. His bucket list includes casting Guillermo del Toro in a film and his gut tells him that he has two more films to make to complete his series, though he’s well aware of the fact that his age and bankability will factor into those ambitions.

As he contemplates that future, Romero admits that doesn’t always “rush out” to screen horror films produced by his contemporaries because some are needlessly cruel. And yes, he suffers the occasional bout of regret when he’s reminded that he turned down the opportunity to direct Scream.

A life well-lived? You bet. The self-described traditional filmmaker likely had no idea that even French filmmakers would come to call his productions essential viewing for anyone seeking to understand American film making.

A final aspect of George Romero’s career bears mentioning because it likely transcends the man’s wildest aspirations: the US Government’s Center for Disease Control has legitimized zombies by setting up a web page on its Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response website. No joke. Zombies on the CDC site? You can thank George Romero for that, too.